[ad_1]

Stefa Jakubowicz and Adolf Weissmark. Catskills, NY, 1965.

Source: Mona Sue Weissmark

As Americans are coping with the aftermath of the pandemic, as well as stressors like crime, inflation, and social inequities, I’ve been remembering my mother’s intimate stories of survival. My mother was a survivor of Auschwitz. Apart from her, every family member (besides a few cousins) was killed by the Nazis. All that remained of my mother’s family tree were a few faded yellow photographs that she kept in an envelope.

Just as I can’t place an exact date on when I first learned to talk or read, I can’t pinpoint exactly when I learned about the Holocaust death camps. However, for as long as I can remember, I have known that my parents, Stefa Jakubowicz and Adolf Weissmark, were survivors of those camps.

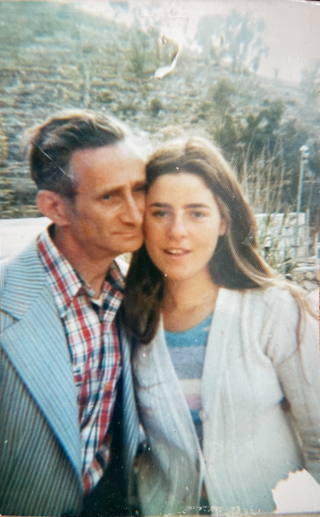

My father and me in Jerusalem,1970’s.

Source: Mona Sue Weissmark

I learned about the past in bits and pieces. My mother would have this inner battle between her desire to tell me about her experiences in Auschwitz and her desire to make my childhood happy. When I would ask her about the blue number #47021 that was visibly tattooed on her forearm, she would say it was there to remember our phone number. She tried to push aside the past for what was, and for her, the far more important task was making sure that her burden didn’t intrude on my happy childhood.

Still, try as she did, the past was always there — an abyss that cried out for an answer. What inquisitive child could avoid wondering how one’s parents had survived the death camps and gotten through Auschwitz remarkably unbroken.

As a young girl, and later as an adult, I tried to make sense of how my mother managed to survive Auschwitz. When she first arrived at Auschwitz, at the age of 18, she had been used to living a comfortable life. Coming from a wealthy family, I wondered how my mother had managed to adapt to such deprivation and dehumanization. So, I pressed her for details on how she survived.

When I was about 13, for the first time I asked my mother this question directly. While I sat at the kitchen table, she stood beside the stove, cutting up potatoes and preparing dinner. I asked, “Mommy, how did you survive Auschwitz?” I knew I was probably being too direct, but I was eager to make sense of the fragments of information that contained such an important history of survival.

My mother explained that the tattoo was her prisoner’s identification number. Initially, in Auschwitz, the numbers were sewn on a prisoner’s clothes. Eventually, though, the death rate was so high that the Nazis needed a more efficient method for identifying corpses. The tattoo numbers served as a better way to keep track of the corpses. It became a synonym for the dehumanization of the prisoners.

My mother explained that when prisoners arrived at Auschwitz, they were either selected for forced labor or immediately sent to the gas chambers. Their heads were shaved, their belongings taken, and then they lined up to receive their tattoo numbers. From this time on, the prisoners did not officially use their names. They became labeled only as numbers. It was the final nail in the cruel «registration» process in Auschwitz. During roll calls in the morning or in the middle of the night, the prisoners had to provide their numbers in German. The survivors of the Holocaust never forgot their numbers.

In telling me more about her tattoo, my mother said, “It was a lucky number.” I was puzzled by her statement. What could possibly be lucky about it, I wondered? It seemed to me that being reduced to a number was a horrific mark of cruelty. There was nothing lucky about it. So, I asked her, “Why do you say it was lucky?”

She knew the time had come to tell me about her past. My questions and genuine interest in knowing her history were a part of me too, and she understood that. Rather than being reluctant, for the first time, she seemed eager to tell the complete story.

My mother continued her narrative and said, “One day, a Nazi guard came into the barracks during roll call with a list and called out my number. I knew what that meant — the next morning I had to get in line with the other prisoners whose numbers were called to be sent to be gassed in the crematorium. But, when the Nazi came the next morning and shouted for everyone whose number was called to line up, my number did not get called to the line.”

Then, my mother smiled. She said, gesturing to me, “I was lucky because, would you believe, the next morning when they came to get us, the Nazi did not have my number on the list. I did not know that when I decided not to get on the line. I took my chances. It was a lucky number. Can you believe it? What are the odds? This never happened before — where they lost the list of numbers.”

She could see by the look on my face that I wasn’t satisfied. When recalling an event in Auschwitz, my mother had the desire to impart a lesson in the narratives she told me. So, she continued, “I figured… when there is nothing to lose, you should take a risk.”

She then continued more factually, “Also, I was lucky because I had a good job. I was in the Canada barracks.” The prisoners gave the concentration camp barracks nicknames. The buildings holding the looted Jewish property were called the “Canada barracks” because Canada was considered the rich New World. When the transports arrived at Auschwitz, the prisoners on the trains were told to climb down with their luggage and deposit it alongside the train. My mother’s job, I learned, was to sort the shoes.

In order to further satisfy my curiosity, she explained, “I was fortunate because it was indoor work and I could trade the shoes for food. If you had things to trade, you were better off. I could buy the best food.” She looked at me in a way that encouraged me to say, “I understand.”

“Are you saying you survived because you were lucky and took risks?” I asked.

She shook her head no and continued matter-of-factly, “I was young, and I wanted to live. If you did not have hope in the camps, then nothing would help you — not luck or taking risks. Some prisoners just gave up. They were unable or unwilling to go on. Some of them ran into the wire.”

I later learned that “ran into the wire” was an expression used in concentration camps to describe one method of suicide — touching the electrically charged barbed wire fence. My mother said, “Other prisoners committed suicide by giving up the will to live, and they turned into walking corpses — in the camps we called them Muselmann.” She explained that “Muselmann” was the slang term used amongst the prisoners in camps to refer to those prisoners who were hopeless and resigned themselves to their impending death.

I was transfixed by the sad image of hopeless prisoners shuffling around the camp. I pushed for her to continue her narrative, and asked, “Really? They gave up and lost all hope?” I tried to hide my urge to cry because crying would break the unspoken agreement between us that the details of her survival would not upset me.

My mother continued her narrative. A new tone had come into her voice. She replied, “I could always tell when someone gave up hope by the way they walked and acted. They were indifferent to their surroundings, and they mentally and physically deteriorated. You could tell just by looking at them that they gave up the will to live. Usually this happened suddenly. They would refuse to eat, to get dressed, to wash or report for roll call. Threats and blows had no effect. Nothing in this world could bother the Muselmann any longer. And, within a few days, they died. It was a sickness born of hopelessness. The prisoner who gave up hope and lost faith was doomed to die.”

The Nazis running the camps considered the Muselmann undesirable because they could not work or endure the camp conditions. So, during selections for the gas chambers, these victims were the first to be sentenced to death. My mother explained that a prisoner at the Muselmann stage had no chance for survival; he or she would not survive in the camps for more than a few days or weeks. My mother explained that the other prisoners would avoid contact with a Muselmann, in fear of contracting their hopeless condition, as if it was contagious.

My mother continued her narrative, “I never gave up. I chose to hope. I remember Leah.” My mother went on, “Leah was my ‘concentration camp sister.’ I would imagine the dinners we would share together when we would be liberated from the camp. We’d set the table, we’d plan the menu, and then we would imagine ourselves safe and together at the table eating a delicious dinner.”

As my mother described this scene, she smiled, and her face lit up with pleasure. It was as though she was telling me about a dinner she had recently enjoyed at a five-star restaurant. She paused and went on, “In Auschwitz, I made myself a promise that I would not give up hope. I imagined that one day I would be released from the camp, and I would tell the world what happened, so that no one would ever suffer again like we suffered — so the world will be more peaceful.”

Stefa Jakubowicz Weissmark and Adolf Weissmark in Montreal,Canada, 1980’s.

Source: Mona Sue Weissmark

My mother, Stefa Jakubowicz Weissmark, inspired me to follow in her footsteps along a path of sharing hope. As a researcher and clinical and social psychologist, I have spent my career studying trauma, human behavior, and motivation. My memories of our conversations and the questions they compelled me to ask have never left me. What was this hope my mother hung on to? Was it a refusal to face reality, naive optimism, wishful thinking… or something else entirely?

The concept of “hope” is sometimes misunderstood. In our everyday language, it often has a hint of uncertainty. For example, we may say we “hope it will be a warm day tomorrow” or we “hope a relative will visit.” Also, popular discourse often takes hope to be synonymous with optimism.

However, the way my mother used “hope” was different. She knew the odds of survival in Auschwitz were slim, and she was keenly aware of the horrible reality around her. My mother’s hope was not based on the empirical data about the probabilities of surviving Auschwitz — rather, it was an attitude by which she expressed both her commitment to a better future and her belief in its possibility. The way my mother hoped went beyond the hard evidence. It was future-directed; it was a forward-looking hope.

She hoped for progress toward a better and more just and peaceful world. She believed in the possibility of a higher good. One can reason, her hope was not irrational because it could not be proven to be impossible. Indeed, the hope for a better future is a rational motivation because without it, the wish to benefit the common good would never have inspired the human heart. Grounded hope encourages us to cope with traumatic experiences instead of succumbing to despair.

Today, we are living through the aftermath of a global pandemic. It may seem counterintuitive, but as we move forward through these difficult times, it can be helpful to look to the stories of Holocaust survivors for direction as to how people have dealt with previous collective traumas. Lessons from past resilience can help us cope with the present adversity. When coping with the pandemic, the focus tends to be on treating and preventing physical illness — and that is important. But, equally important, are the mental effects of loss and isolation that have come with the pandemic, and which have taken psychological and emotional tolls.

The data show that the psychological, emotional consequences of the pandemic are devastating. The number of Americans seeking treatment for anxiety and depression has soared, creating what a leading medical association terms a “mental health tsunami.” Nearly half of Americans say that COVID-19 has affected their mental health, according to a recent poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation (McCoy, 2021).

The same survey also found an increased demand for help with other mental health issues, including sleep disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorders, and substance-related and addictive disorders. Also, the U.S. Surgeon General recently issued an advisory to highlight the urgent need to address the nation’s youth mental health crisis. Given the magnitude of our current mental health crisis, a better understanding of hope can help us as a collective strategy for managing our mental health.

Research suggests that hope is a resiliency factor that can promote well-being during a global health crisis (Gallagher et al., 2021). Hope has also been associated with fewer posttraumatic symptoms (PTSD) of depression and anxiety, and data from a meta-analytic review show that hope acts as a protective factor against developing chronic or severe symptoms of PTSD (Arnau et al., 2007; Gallagher et al., 2020).

The research suggests that people who are high in hope are more likely to make skillful changes to life’s challenges and to use effective coping strategies in the face of adversity (Lee & Gallagher, 2018). In this way, hope may stimulate increased positive affect, life satisfaction, and success, especially during times of stress, such as the pandemic. Importantly, hope may protect against states of helplessness, uncertainty, and a perceived inability to predict, control, or obtain desired results. These findings suggest that hope is associated with resilience to the chronic stressors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

My mother and me at age 4. Vineland, New Jersey.

Source: Mona Sue Weissmark

I once asked my mother how she could continue to have faith in God, given all the suffering she endured and all the cruelty she witnessed in Auschwitz.

My mother responded, “After I was liberated from Auschwitz, I stopped having faith and felt it was my right to give it up because so many innocent people were killed for no reason. But, later I realized that if I gave up my faith, then the Nazis would have won. I did not want them to take away my humanity. My decision to have faith and hope is needed for a better future.”

Given the duration and global nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is likely to have a lasting impact on our society. While we have developed an understanding of how to prevent and treat negative physical illness outcomes, it is just as important to determine what factors of resilience may help support mental health well-being and to protect against or reduce levels of stress and anxiety.

What my mother understood and what she passed on to me wasn’t only a factual narrative of living in Auschwitz, it was also a path for survival and resilience. A forward-oriented trait, such as hope, can help us look toward the possibilities for a better future, rather than to be consumed by the memories of the past or the obstacles of the present.

Copyright 2022 All Rights Reserved Mona Sue Weissmark

[ad_2]

Source link